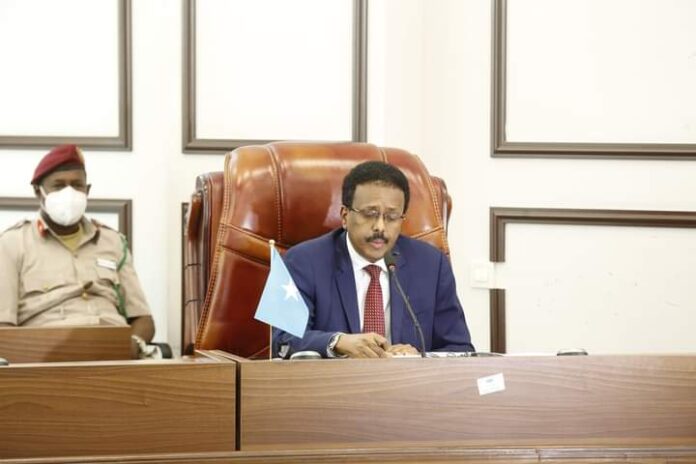

With a long-running Islamist insurgency and elections delayed for months, Somalia is no stranger to instability, but the country now faces the risk of renewed violence because of an increasingly bitter stand-off between its president and prime minister.

Here is a look at why relations between Prime Minister Mohamed Hussein Roble and President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed, alias Farmaajo, deteriorated so quickly and what lies ahead for the volatile Horn of Africa nation.

Was their relationship always difficult?

Not quite. A Swedish-trained civil engineer, Roble was plucked out of political obscurity by the president, better known as Farmaajo, who appointed him premier last September.

The technocrat generally took a backseat to the politically savvy Farmaajo, who worked in the Foreign Affairs ministry and served as premier himself before becoming president.

After the head of state extended his mandate in April without holding elections, triggering the country’s worst bout of political violence in years, he turned to Roble to help defuse the situation by asking him to organise the parliamentary polls.

What went wrong?

As Roble’s profile rose, he began to challenge Farmaajo on several issues, angering the president.

He visited Kenya last month, flagging a thaw in diplomatic ties, days after Farmaajo banned government institutions or officials from entering into agreements with foreign countries or entities until elections were held.

Roble then took on Somalia’s powerful National Intelligence and Security Agency (NISA) last week, criticising its handling of a high-profile investigation into the fate of a 25-year-old officer, Ikran Tahlil, whose disappearance prompted an outcry.

Tahlil’s family has accused NISA of murdering her — a view backed by many Somalis who have taken to social media to denounce the agency and demand justice.

When Roble suspended the agency’s director, Fahad Yasin, a close associate of Farmaajo, the president reacted swiftly, first reinstating and then promoting his old friend to the position of national security adviser.

The prime minister responded by accusing Farmaajo of “obstructing” the probe, and said the developments signalled “a dangerous existential threat to the country’s governance system”.

Where do things stand now?

The public spat has raised tensions in Mogadishu, where military units close to Farmaajo’s office were seen stationed outside NISA headquarters Wednesday.

The infighting has also had a knock-on effect on various government bodies, with one NISA officer telling AFP that senior officials had apparently picked sides in the row.

A Ministry of Information staffer told AFP that journalists at state-run media outlets were being instructed not to broadcast messages from Farmaajo.

On Wednesday night, matters escalated further when Roble sacked Internal Security Minister Hassan Hundubey Jimale and replaced him with a Farmaajo critic, saying the move would “revitalise” the key ministry, which oversees all security, police and intelligence agencies.

The president wasted no time in firing back Thursday, calling the decision unconstitutional, while the dismissed minister accused Roble of dragging the country “into a new conflict”.

What lies ahead?

Many fear the spat will throw an already fragile electoral process into deeper peril.

The next phase of the election, which follows a complex indirect model of voting, is set to kick off for the lower house of parliament between October 1 and November 25.

But it is not clear when parliament will elect a new head of state.

“This conflict, if not resolved amicably, will complicate every other ongoing political effort including the election process, which will be delayed if not completely stopped,” Abdikani Omar, a former high-ranking civil servant, told AFP.

Roble has already accused Farmaajo of trying to reclaim “the election and security responsibilities” entrusted to him earlier this year.

Why does it matter?

With Al-Shabaab jihadists controlling large areas of the country, Somalia is in no position to cope with a full-blown political crisis.

Somalia’s intelligence agency is an essential weapon in its fight against the Al-Qaeda-linked insurgents, who will be quick to exploit any sign of weakness.

The militants have already waded into the row, issuing a swift — and unusual — denial when NISA said its young officer had been murdered by the group.

The international community is worried, with the United Nations, the African Union Mission in Somalia (Amisom), the United States, the European Union and East African bloc Igad among those urging the two men to stop bickering and focus on the country.

A decade after the Al-Qaeda-linked militants were ousted from Mogadishu, the government controls only a small portion of the country, with the crucial help of some 20,000 soldiers from Amisom.

“We saw back in April how quickly Mogadishu can become a theatre for opposing military forces amid a wider political breakdown,” said Omar Mahmood, a senior analyst at the International Crisis Group (ICG).

“Depending on how events unfold in the coming days, a repeat situation could be in the offing.”